Advanced GDB Usage

About 6 years ago, when I was in my first few months at Pebble as a firmware engineer, I decided to take an entire workday to read through the majority of the GDB manual. It was by far one of my best decisions as an early professional engineer. After that day, I felt like I was 10x faster at debugging the Pebble firmware and our suite of unit tests. I even had a new .gdbinit script with a few macros and configuration flags to boot, which I continue to amend to this day.

Over the years, I’ve learned from many firmware developers and am here writing this post to share what I’ve learned along the way. If you have any comments or suggestions about this post, I would love to hear from you in Interrupt’s Slack channel.

In this reference-style post, we discuss some of the more advanced and powerful commands of the GNU debugger, GDB, as well as cover some of the best practices and hacks I’ve found over the years that help make GDB more pleasant to use.

Although there might be debuggers and interfaces out there that provide better experiences than using GDB directly, many of them are built on top of GDB and provide raw access to the GDB shell, where you can build and use automation through the Python scripting API.

At the end of most of the sections, there are links to either subpages with the GDB manual or to the original content to learn more about the topic discussed.

Table of Contents

Essentials

First, we need to cover the items which I feel are most important for any developer or team to work efficiently within GDB.

Navigate the Help Menus

There’s no better place to start learning GDB than to first learn how to search the help menus. Surprisingly, or maybe unsurprisingly, GDB has over 1500+ commands!

# Count number of GDB commands in the master help list

$ gdb --batch -ex 'help all' | grep '\-\-' | wc

1512 16248 117306

With this in mind, the most useful command within GDB is apropos, which searches all the “help” menus of each command. To use it, simply type apropos <regex>.

(gdb) apropos symbol

add-symbol-file -- Load symbols from FILE, assuming FILE has been dynamically loaded.

add-symbol-file-from-memory -- Load the symbols out of memory from a dynamically loaded object file.

attach -- Attach to a process or file outside of GDB.

...

To get the individual help menu of any command in GDB, just type help <command>, and GDB will output everything it knows about the command or subcommand.

(gdb) help apropos

Search for commands matching a REGEXP

If help is used on a collection of commands:

(gdb) help info

Generic command for showing things about the program being debugged.

List of info subcommands:

info address -- Describe where symbol SYM is stored.

info all-registers -- List of all registers and their contents, for selected stack frame.

info args -- All argument variables of current stack frame or those matching REGEXPs.

...

GDB History

Next, we need to ensure that command history is enabled.

By default GDB does not save any history of the commands that were run during each session. This is especially annoying because GDB supports CTRL+R for history search just like your shell!

To fix this, we can place the following in our .gdbinit.

set history save on

set history size 10000

set history filename ~/.gdb_history

With this in place, GDB will now keep the last 10,000 commands in a file ~/.gdb_history.

Sharing .gdbinit Files

I’m a huge believer in developer productivity, and I try my best to share my best-practices with co-workers and the greater community. In the past, I’ve made it a point to have per-project GDB configuration files that are automatically loaded for everyone by default.

This could be in a bash script debug.sh which developers use instead of typing gdb and all the arguments by hand:

#!/bin/sh

gdb build/symbols.elf \

-ix=./gdb/project.gdbinit \

--ex='source ./gdb/extra_gdb.py' \

"$@"

Better yet, you can build a Project CLI using Invoke which wraps the GDB invocation into an invoke debug command.

This ensures that everyone working on the project has the latest set of configuration flags and GDB Python scripts to accelerate their debugging.

Source Files

With the essentials out of the way, let’s dive into learning GDB! The first thing to talk about is how best to view and navigate the source code while debugging.

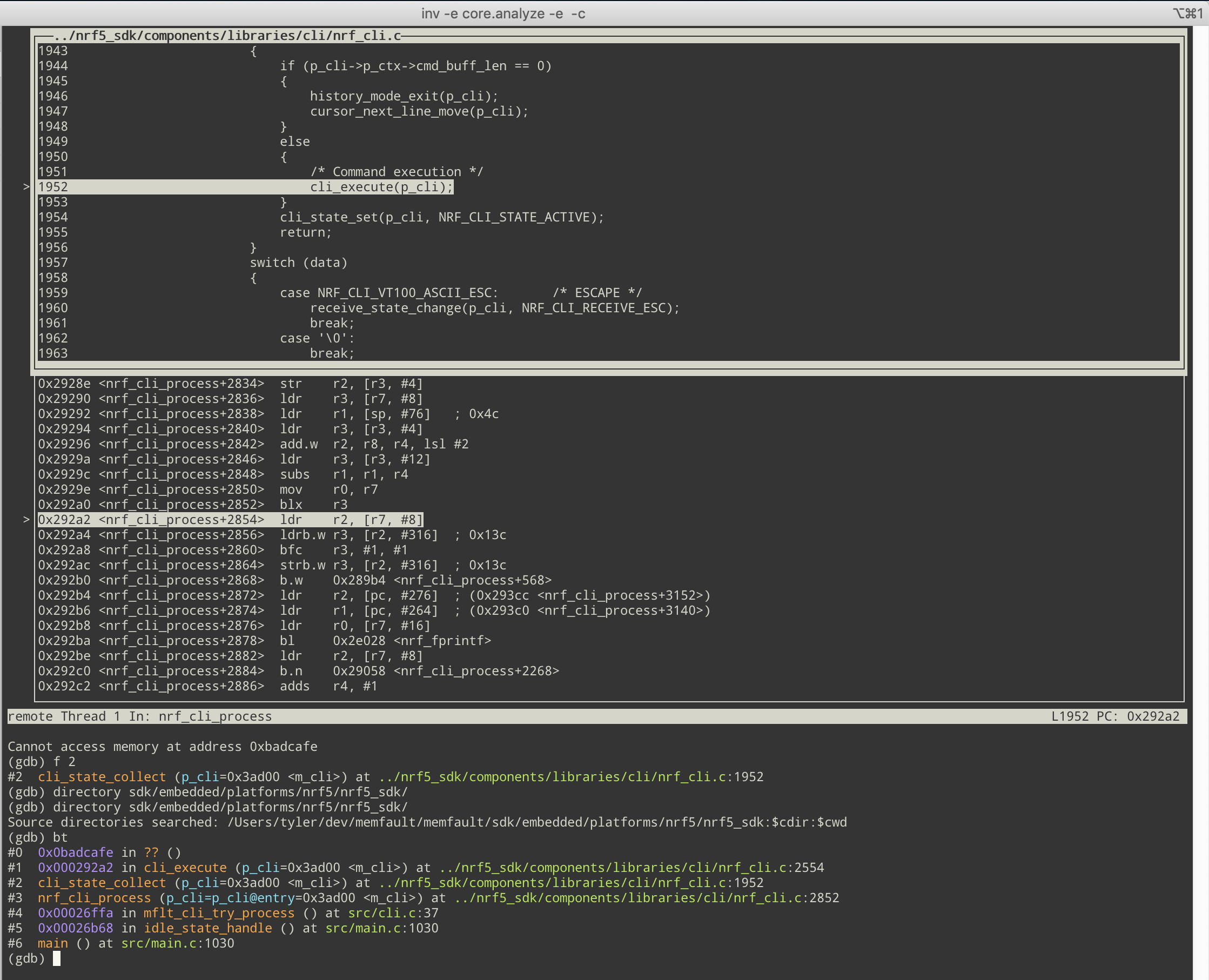

Directory Search Paths

Many times, the CI system builds with absolute paths instead of paths relative to the project root, which causes GDB not to be able to find the source files.

It will produce an error like below:

(gdb) f 1

#2 cli_state_collect (p_cli=0x3ad00 <m_cli>) at

../nrf5_sdk/components/libraries/cli/nrf_cli.c:1952

1952 ../nrf5_sdk/components/libraries/cli/nrf_cli.c:

No such file or directory.

If you are proactive and want to fix this permanently in the build step, you can follow the steps in Interrupt’s post about Reproducible Firmware Builds to make the paths relative.

If you want to patch it up now in GDB, you can use a combination of the set substitute-path and directory commands in GDB, depending on how the paths are built.

To fix the above issue, all I needed to do was to add a local directory. After adding it, GDB can find the source code of the line in the frame.

(gdb) directory sdk/embedded/platforms/nrf5/nrf5_sdk/

Source directories searched: /[...]/sdk/embedded/platforms/nrf5/nrf5_sdk:$cdir:$cwd

(gdb) f 1

#1 0x000292a2 in cli_execute (p_cli=0x3ad00 <m_cli>) at

../nrf5_sdk/components/libraries/cli/nrf_cli.c:2554

2554 p_cli->p_ctx->p_current_stcmd->handler(p_cli,

Source Context with list

Sometimes, you just want to quickly add a few lines above and below the current line. To quickly view ten lines of source-code context within GDB, you can use the list command.

(gdb) list

2549 &p_static_entry,

2550 &static_entry);

2551

2552 p_cli->p_ctx->p_current_stcmd = p_static_entry;

2553

2554 p_cli->p_ctx->p_current_stcmd->handler(p_cli,

2555 argc - cmd_handler_lvl,

2556 &argv[cmd_handler_lvl]);

2557 }

2558 else if (handler_cmd_lvl_0 != NULL)

If you want to set a larger or smaller default number of lines shown with this command, you can change the setting:

(gdb) set listsize 20

Viewing Assembly With disassemble

It’s often useful to dive into the assembly of a specific function. GDB has this capability built-in and can even interleave the source code with the assembly (by using the /s option).

(gdb) disassemble /s nrf_cli_cmd_echo_on

Dump of assembler code for function nrf_cli_cmd_echo_on:

nrf_cli.c:

3511 {

3512 if (nrf_cli_build_in_cmd_common_executed(p_cli, (argc != 1), NULL, 0))

0x0002969c <+0>: ldr r3, [r0, #8]

0x0002969e <+2>: ldr.w r2, [r3, #316] ; 0x13c

nrf_cli.h:

604 return p_cli->p_ctx->internal.flag.show_help;

0x000296a2 <+6>: lsls r2, r2, #30

0x000296a4 <+8>: bmi.n 0x296b8 <nrf_cli_cmd_echo_on+28>

nrf_cli.c:

3391 if (arg_cnt_nok)

0x000296a6 <+10>: cmp r1, #1

0x000296a8 <+12>: bne.n 0x296bc <nrf_cli_cmd_echo_on+32>

If you want something more powerful than disassemble, you can use objdump itself. Interrupt’s post on GNU Binutils is a great reference for this.

GDB Visual Interfaces

There are many visual interfaces that are built into or on top of GDB. Let’s go through a few of the most popular ones.

GDB TUI

GDB has a built-in graphical interface for viewing source code, registers, assembly, and other various items, and it’s quite simple to use!

You can start the TUI interface by running:

(gdb) tui enable

This should give you the source code viewer. You are now able to type next, step, continue, etc. and the TUI interface will update and follow along.

If you want to view the assembly as well, you can run:

(gdb) layout split

To show the registers at the top of the window, you can type:

(gdb) tui reg general

Alternate GDB Interfaces

Although TUI is nice, I don’t know many people who use it and see it more as a gimmick. It’s great for quick observations and exploration, but I would suggest spending the 15-30 minutes to get something set up that is more powerful and permanent.

I would suggest looking into using gdb-dashboard or Conque-GDB if you’d like to stick with using GDB itself.

For a full list of GUI enhancements to GDB, you can check out the list of plugins from my previous post on GDBundle.

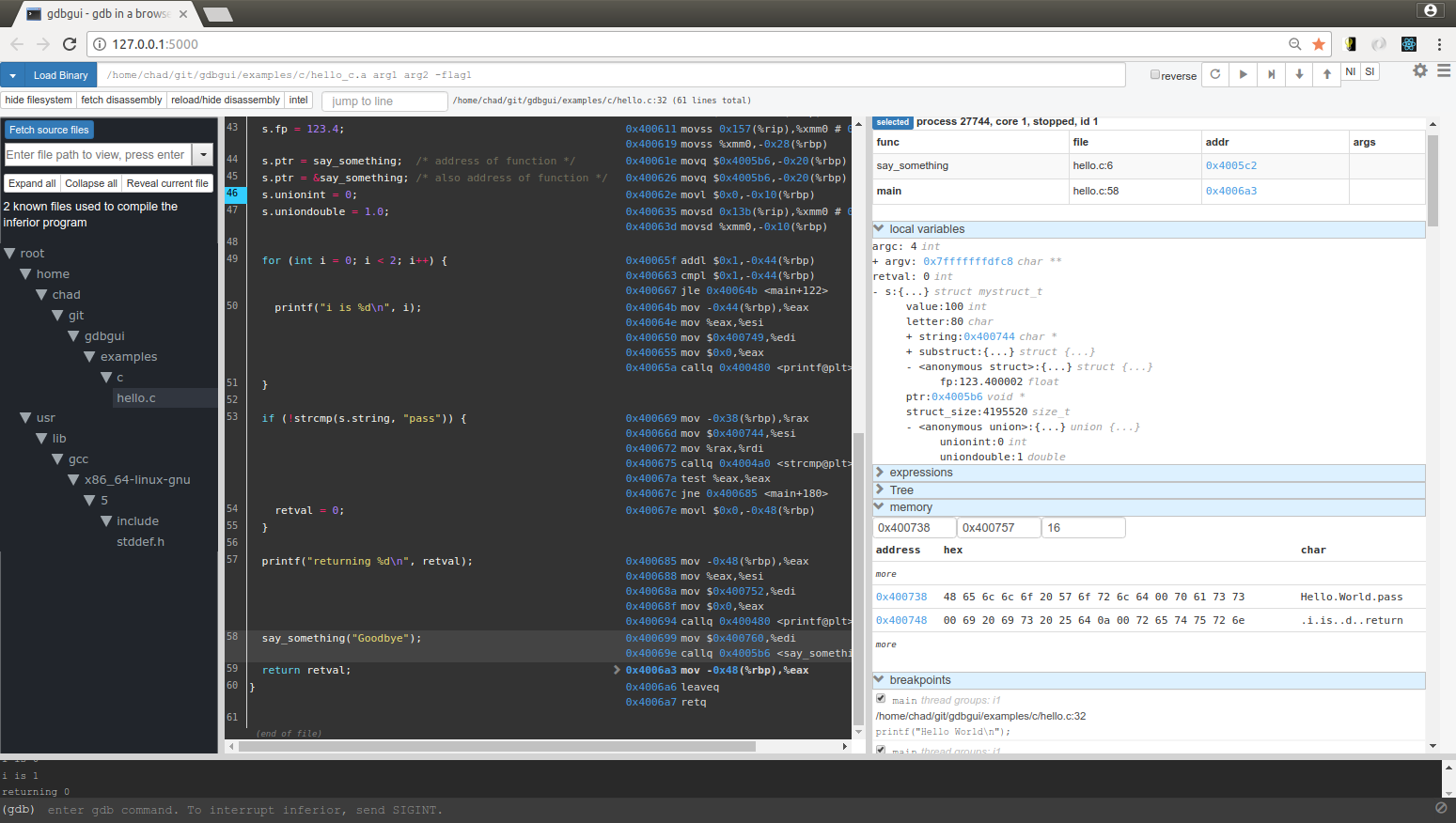

gdbgui

gdbgui is a browser-based frontend to GDB, built by Chad Smith, who also happens to be the author of another one of my favorite tools, pipx.

gdbgui is great tool if you don’t want to use a vendor-provided debugger but still want to have a visual way to interface with GDB.

VSCode

VSCode has pretty good support for GDB baked in. If you are just using GDB to debug C/C++ code locally on your machine, you should be able to follow the official instructions.

If you are looking to do remote debugging on devices connected with OpenOCD, PyOCD, or JLink, you’ll want to look into the Platform.io or Cortex-Debug extensions.

Registers

The next topic to cover is interacting with registers through GDB.

Printing Registers

You can print the register values within GDB using info registers.

(gdb) info registers

r0 0x2 2

r1 0x7530 30000

r2 0x10000194 268435860

r3 0x1 1

r4 0x8001dd9 134225369

r5 0xa5a5a5a5 -1515870811

r6 0xa5a5a5a5 -1515870811

r7 0x20002ad8 536881880

r8 0xa5a5a5a5 -1515870811

r9 0xa5a5a5a5 -1515870811

r10 0xa5a5a5a5 -1515870811

r11 0xa5a5a5a5 -1515870811

r12 0xffffffff -1

sp 0x20002ad8 0x20002ad8 <ucHeap1.14288+7812>

lr 0x8026563 134374755

pc 0x802f03c 0x802f03c <vPortEnterCritical+32>

xpsr 0x10d0000 17629184

fpscr 0x0 0

msp 0x20017fe0 0x20017fe0

psp 0x20002ad8 0x20002ad8 <ucHeap1.14288+7812>

primask 0x0 0

control 0x6 6

You can also use info registers all if there are more registers on your system that aren’t printed by default, but do note they may or may not be valid values (depending on your system and gdbserver).

Register Variables

GDB provides you access to the values of the system registers in the form of variables, such as $pc or $sp for the program counter or stack pointer.

When we want to reference these registers directly, we can just use $<register_name>!

(gdb) p $sp

$2 = (void *) 0x20002ad8 <ucHeap1.14288+7812>

(gdb) p $pc

$3 = (void (*)()) 0x802f03c <vPortEnterCritical+32>

Notice these are the same values as above when we used info registers.

If your gdbserver supports it, you can also set these register values! This is really useful for when you are trying to debug a hard fault and all you have are the sp, lr, and pc registers.

(gdb) set $pc = <pc from fault handler>

(gdb) set $lr = <lr from fault handler>

(gdb) set $sp = <sp from fault handler>

# Hopefully now a real backtrace!

(gdb) bt

Memory

Listing Memory Regions

It’s possible to list the memory regions of the binary currently being debugged by running the info files command.

(gdb) info files

Symbols from "symbols/zephyr.elf".

Local exec file:

`symbols/zephyr.elf', file type elf32-littlearm.

Entry point: 0x8009e94

0x08000000 - 0x080001c4 is text

0x080001d0 - 0x0802cb6e is _TEXT_SECTION_NAME_2

0x0802cb70 - 0x0802cb78 is .ARM.exidx

0x0802cb78 - 0x0802ce08 is sw_isr_table

0x0802ce08 - 0x0802cfac is devconfig

0x0802cfac - 0x0802cfb8 is net_socket_register

0x0802cfb8 - 0x0802d098 is log_const_sections

0x0802d098 - 0x0802d0a8 is log_backends_sections

0x0802d0a8 - 0x0802d0e8 is shell_root_cmds_sections

0x0802d0e8 - 0x08036e98 is rodata

0x20000000 - 0x2000a1f5 is bss

0x2000a200 - 0x2001112b is noinit

0x2001112c - 0x200113f1 is datas

...

0x200117c0 - 0x200117e0 is net_if_dev

This is especially helpful when you are trying to figure out exactly where a variable exists in memory.

Examine Memory using x

Many developers know how to use GDB’s print, but less know about the more powerful x (for “examine”) command. The x command is used to examine memory using several formats.

My most common use of x is looking at the stack memory of a system that doesn’t have a valid backtrace in GDB. If we know the stack area name and size, we can quickly print the entire contents and see if there are valid function references.

I’m looking at a Zephyr RTOS based system and one of the stack regions is called my_stack_area. Let’s dump the entire contents.

First we find the size of the stack:

(gdb) p sizeof(my_stack_area)

$1 = 2980

It’s 2980 bytes, so we want to print 2980/4 = 745 words. That should be x/745a then.

(gdb) x/745a my_stack_area

0x2000a3c0 <my_stack_area>: 0xaaaaaaaa 0xaaaaaaaa 0xaaaaaaaa 0xaaaaaaaa

0x2000a3d0 <my_stack_area+16>: 0xaaaaaaaa 0xaaaaaaaa 0xaaaaaaaa 0xaaaaaaaa

... A lot more 0xaaaaaaaa

0x2000a8d0 <my_stack_area+1296>: 0xaaaaaaaa 0xaaaaaaaa 0x190 0x2000a900 <my_stack_area+1344>

0x2000a8e0 <my_stack_area+1312>: 0x18f 0x0 0x2000a298 <my_stack_area2+152> 0x18f

0x2000a8f0 <my_stack_area+1328>: 0x20000434 <my_work_q> 0x8021063 <process_accel_data_worker_task> 0x0 0x802108d <process_accel_data_worker_task+42>

0x2000a900 <my_stack_area+1344>: 0x1 0x20002 0x40002 0x60002

0x2000a910 <my_stack_area+1360>: 0x80002 0xc0004 0x100004 0x160006

0x2000a920 <my_stack_area+1376>: 0x1c0006 0x240008 0x2c0008 0x38000c

... A lot of accel int32_t readings

0x2000af30 <my_stack_area+2928>: 0x92f5648a 0xf83c6547 0x5d9a654f 0xc39f6605

0x2000af40 <my_stack_area+2944>: 0x0 0x8021505 <z_work_q_main+68> 0x0 0x80214c1 <z_work_q_main>

0x2000af50 <my_stack_area+2960>: 0x0 0x80214b9 <z_thread_entry+12> 0x0 0xaaaaaaaa

0x2000af60 <my_stack_area+2976>: 0xaaaaaaaa

We can easily see some references to functions in this stack, such as process_accel_data_worker_task, z_work_q_main, and z_thread_entry. This stack dump technique is especially useful if your GDB provides you with no backtrace information, such as:

(gdb) bt

#0 0x00015f5a in ?? ()

Searching Memory using find

Sometimes you know a pattern that you are looking for in memory, and you want to quickly find out if it exists in memory on the system. Maybe it’s a magic string or a specific 4-byte pattern, like 0xdeadbeef.

Let’s search for the string shell_uart, which is the task name of a thread in my Zephyr system. I’ll search the entire writeable RAM space, which can be found by running the info files command mentioned previously.

(gdb) find 0x20000000, 0x200117e0, "shell_uart"

0x2000121c <shell_uart_thread+104>

1 pattern found.

If we use x/s to examine that memory, we can see that it is indeed shell_uart.

(gdb) x/s 0x2000121c

0x2000121c <shell_uart_thread+104>: "shell_uart"

The find command can also be useful for finding pointers pointing to arbitrary structs. For example, I want to find all the pointers that contain a reference to the variable mgmt_thread_data.

(gdb) find 0x20000000, 0x200117e0, &mgmt_thread_data

0x20002a18 <tx_classes+120>

0x2000d068 <mgmt_stack+648>

0x2000d074 <mgmt_stack+660>

0x2000d088 <mgmt_stack+680>

0x2001169c <network_event>

0x200116a0 <network_event+4>

6 patterns found.

It looks like there are some references on the mgmt_stack, and a few other references, which are actually pointers from linked lists.

Using find can help track down memory leaks, memory corruption, and possible hard faults by seeing what pieces of the system are continuing to reference memory or values when they shouldn’t.

Hex Dump with xxd

I love xxd for printing files in hexdump format in the shell, but GDB doesn’t have anything similar built-in Below is a bit of a hack to bring xxd into GDB but it works perfectly.

define xxd

dump binary memory /tmp/dump.bin $arg0 ((char *)$arg0)+$arg1

shell xxd /tmp/dump.bin

end

document xxd

Runs xxd on a memory ADDR and LENGTH

xxd ADDR LENTH

end

If I place the above in my .gdbinit, I should now have a command xxd in GDB that I can use to hexdump an address and length.

(gdb) xxd &shell_uart_out_buffer sizeof(shell_uart_out_buffer)

00000000: 6d66 6c74 3e68 656c 700a 6372 6173 680a mflt>help.crash.

00000010: 6163 6365 6c65 726f 6d65 7465 720a 7761 accelerometer.wa

00000020: 7463 6864 6f67 0a74 696d 6572 730a 6578 tchdog.timers.ex

00000030: 6974 0a it.

I find this most useful when dumping the contents of log buffers, but it is a great compliment to using the x command to see if a binary buffer contains ASCII data.

Variables

Next up, let’s learn to find and print out any variable on the system.

Searching for Variables

To print the local and argument variables, we can use info locals and info args.

(gdb) info locals

i = 400

tmp = {1, 222, 7, 84}

(gdb) info args

raw_samples = 0x3128115f

dft_out = 0x2000a900 <my_stack_area+1344>

num_samples = 536912536

You can also print all static and global variables in the system by using info variables, but that will print a lot of variables out to your screen. It’s better to filter through them!

The command info variables can optionally take a regular expression that will perform a search against the name of the variable.

(gdb) info variables coredump*

All variables matching regular expression "coredump":

File components/core/src/memfault_data_packetizer.c:

40: const sMemfaultDataSourceImpl g_memfault_coredump_data_source;

File components/panics/src/memfault_coredump.c:

392: const sMemfaultDataSourceImpl g_memfault_coredump_data_source;

File ports/panics/src/memfault_platform_ram_backed_coredump.c:

48: static uint8_t s_ram_backed_coredump_region[700];

...

It’s also possible to have the regular expression apply to the type as well! Just add -t before the regex.

(gdb) info variables -t k_spinlock

All defined variables with type matching regular expression "k_spinlock" :

File zephyr/drivers/timer/cortex_m_systick.c:

41: static struct k_spinlock lock;

File zephyr/kernel/mem_slab.c:

17: static struct k_spinlock lock;

File zephyr/kernel/mempool.c:

16: static struct k_spinlock lock;

...

Referencing Specific Variables

If you work on a large project with many modules, you’ll likely have static and global variables with the same name.

(gdb) info variables lock

File zephyr/zephyr/kernel/mempool.c:

16: static struct k_spinlock lock;

File zephyr/zephyr/kernel/mutex.c:

46: static struct k_spinlock lock;

File zephyr/zephyr/kernel/poll.c:

36: static struct k_spinlock lock;

...

You can reference specific variables from specific files using the following syntax:

(gdb) p &'mempool.c'::lock

$4 = (struct k_spinlock *) 0x20002370 <lock>

(gdb) p &('mutex.c'::lock)

$8 = (struct k_spinlock *) 0x2000a0c4 <lock>

You can also reference specific variables from functions using a similar syntax. This is most helpful for referencing static variables within functions from the global context.

For example, in the Memfault Firmware SDK, we have a function ``memfault_platform_coredump_get_regionswhich contains a static variables_coredump_regions`. Source

In GDB, we are unable to print that variable directly:

(gdb) p s_coredump_regions

No symbol "s_coredump_regions" in current context.

But, if we reference the function directly, we can print the value:

(gdb) p memfault_platform_coredump_get_regions::s_coredump_regions

$3 = {{

type = kMfltCoredumpRegionType_Memory,

region_start = 0x0,

region_size = 0

}}

Value History Variables

Every time you print an expression in GDB, it will print the value, but in the format of$<integre> = <value>.

(gdb) p "hello"

$1 = "hello"

The $1 is a variable, which you can use at any point in the debugging session in other expressions and functions. Every new print statement will get its own variable and the numbers will continuously increase.

(gdb) p $1

$2 = "hello"

Can’t remember exactly which variable existed in the past? Just use show values to print the most recent ten.

(gdb) show values

$1 = 800

$2 = 2980

$3 = (uint32_t *) 0x3128115f

$4 = (uint32_t *) 0x2000a900 <my_stack_area+1344>

$5 = 536912536

$6 = 400

Convenience Variables

GDB also allows you to create and retrieve any number of variables within a debugging session. All you need to do is use set $<name> and then you can print these out or use them in expressions.

(gdb) set $test = 5

(gdb) p $test

$4 = 5

These are useful when you are using complex expressions, possibly involving casts and nested structs, that you want to recall later.

(gdb) set $wifi = mgmt_thread_data.next_thread.next_thread

(gdb) p $wifi

$11 = (struct k_thread *) 0x200022ac <eswifi_spi0+20>

You can also use convenience variables to help you print fields within an array of structs.

(gdb) p &shell_wifi_commands

$37 = (const struct shell_static_entry (*)[5]) 0x8031650 <shell_wifi_commands>

The above array is a list of shell_static_entry structs, each of which has many fields. Browsing through lists of structs is sometimes cumbersome, especially if I’m only trying to look at a single field.

Convenience variables can help with this.

Let’s print the help element from struct in the array. I’ll set $i = 0 as my index counter and use $i++ in each command so that it increments.

(gdb) set $i = 0

(gdb) print shell_wifi_commands[$i++]->help

$1 = 0x80314e0 "\"<SSID>\"\n<SSID length>\n<channel number (optional), 0 means all>\n<PSK (optional: valid only for secured SSIDs)>"

(gdb) <enter>

$2 = 0x803155c "Disconnect from Wifi AP"

...

Each time I press enter, the previous command is executed and i increments, printing me the data in the next struct in the array.

The $ Variable

In GDB, the value of $ is the value returned from the previous command.

(gdb) p "hello"

$63 = "hello"

(gdb) p $

$64 = "hello"

This is useful in its own right, but it is especially useful for helping me with one of my least favorite tasks in GDB: iterating over linked lists.

You may have done something similar to the following:

(gdb) p mgmt_thread_data.next_thread

$65 = (struct k_thread *) 0x2000188c <eswifi0+48>

(gdb) p mgmt_thread_data.next_thread.next_thread

$66 = (struct k_thread *) 0x200022ac <eswifi_spi0+20>

Instead of adding .next_thread onto the end of the list each iteration, you can use the value of $ and just keep pressing <enter>.

(gdb) p mgmt_thread_data.next_thread

$67 = (struct k_thread *) 0x2000188c <eswifi0+48>

(gdb) p $.next_thread

$68 = (struct k_thread *) 0x200022ac <eswifi_spi0+20>

(gdb) <enter>

$69 = (struct k_thread *) 0x2000a120 <k_sys_work_q+20>

Artificial Arrays

It is often useful to print a contiguous region of memory as if it were an array. A common occurrence of this is when using malloc to allocate a buffer for a list of integers.

int num_elements = 100;

int *elements = malloc(num_elements * sizeof(int));

In GDB, if you try to print this, it will just print the pointer value, since it doesn’t know it’s an array.

(gdb) p num_elements

$1 = 100

(gdb) p elements

$2 = (int *) 0x5575e51f6260

We can print this entire array using one of two ways. First, we can cast it to a int[100] array and print that.

(gdb) p (int[100])*elements

$10 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ...

Or we can use GDB’s artificial arrays! An artificial array is denoted by using the binary operator @. The left operand of @ should be the first element in thee array. The right operand should be the desired length of the array.

(gdb) p *elements@100

$11 = {0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, ...

Conditional Breakpoints and Watchpoints

A conditional breakpoint in GDB follows the format break WHERE if CONDITION. It will only bubble up a breakpoint to the user if CONDITION is true.

Let’s imagine we are trying to triage a reproducible memory corruption bug. You don’t exactly know when or how a num_samples argument is being corrupted with the value of 0xdeadbeef when the function compute_fft is called. We can improve our investigation using conditional breakpoints.

(gdb) break compute_fft if num_samples == 0xdeadbeef

You can use register values ($sp, $pc, etc.) in the conditional expressions as well.

Note that the expressions are evaluated host side within GDB, so the system halts every time, but GDB will only prompt the user when the expression is true. Therefore, system performance might be impacted.

You can also do the same with watchpoints, which will only prompt the user in GDB if the conditional is true.

(gdb) watch i if i == 100

(gdb) info watchpoints

Num Type Disp Enb Address What

1 hw watchpoint keep y i stop only if i == 100

Backtrace for All Threads

To quickly gain an understanding of all of the threads, you can print the backtrace of all threads using the following:

(gdb) thread apply all bt

# Shortcut

(gdb) taa bt

In my personal .gdbinit, I have the following alias set to btall.

# Print backtrace of all threads

define btall

thread apply all backtrace

end

Reference Bonus Reference for Backtrace Formatting

Pretty Printers

GDB Pretty Printers are essentially printing plugins that you can register with GDB. Every time a value is printed in GDB, GDB will check to see if there are any registered pretty printers for that type, and will use it to print instead.

For instance, imagine we have a struct Uuid type in our codebase. `

typedef struct Uuid {

uint8_t bytes[16];

} Uuid;

If we print this, we’ll get the following:

(gdb) p *(Uuid *)uuid

$6 = {

bytes = "\235]D@\213Z#^\251\357\354?\221\234zA"

}

That’s pretty useless to us as we can’t read it like a UUID should be written. It would be great if it was printed in the form of xxxxxxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxx-xxxxxxxxxxxx. Pretty printers to the rescue!

After writing a custom pretty printer using GDB’s Python API, our UUID’s will be printed in a human-readable format.

(gdb) p *(Uuid *)uuid

$6 = {

bytes = 9d5d4440-8b5a-235e-a9ef-ec3f919c7a41

}

Struct Operations

sizeof

You can easily get the size of any type using sizeof within GDB, as you would in C.

(gdb) p sizeof(struct k_thread)

$5 = 160

offsetof

This isn’t a built-in command, but it’s easy enough to add a small macro for it.

(gdb) macro define offsetof(t, f) &((t *) 0)->f

This macro can also be placed directly within a .gdbinit file.

With this in place, we can now print the offset of any struct members.

(gdb) p/d offsetof(struct k_thread, next_thread)

$3 = 100

Interactions Outside of GDB

Run Make within GDB

Executing the command make directly in GDB will trigger Make from the current working directory.

(gdb) pwd

Working directory /Users/tyler/nrf5/apps/memfault_demo_app.

(gdb) make

Compiling file: arch_arm_cortex_m.c

Compiling file: memfault_batched_events.c

...

Running Shell Commands

You can also run arbitrary shell commands within GDB. This is especially useful to me when I’m working on my firmware projects because I always wrap Make with an Invoke-based CLI for building and debugging my projects.

(gdb) shell invoke build

Compiling file: arch_arm_cortex_m.c

Compiling file: memfault_batched_events.c

Outputting to File

You can output GDB’s stdout to a file by using GDB’s built-in logging functionality.

(gdb) set logging on

Copying output to gdb.txt.

Copying debug output to gdb.txt.

Now, any command you run during this session will have its output written to this file as well.

(gdb) p "hello"

$1 = "hello"

(gdb) quit

$ cat gdb.txt

$1 = "hello"

quit

This is most useful when you have a GDB script or Python command that outputs structured data, such as JSON, which you want to then use outside of the GDB session.

Embedded Specific Enhancements

Thread Awareness

If you are using PyOCD, OpenOCD, or JLink, ensure you are using a gdbserver that is compatible with your RTOS so that you can get the backtraces for all threads.

For OpenOCD and PyOCD, you can view their supported RTOS’s and source code for them in Github (OpenOCD, PyOCD)

To integrate an RTOS with Jlink, you’ll have to either use ChibiOS or FreeRTOS, which they support by default, or write your own JLink RTOS plugin. You can reference Github to gain an understanding of how to write one.

SVD Files and Peripheral Registers

With the help of PyCortexMDebug, you can parse SVD files and read peripheral register values more easily. To get started, first acquire the .svd file from your vendor or look at the cmsis-svd repo on Github.

Once you have the file, clone the PyCortexMDebug repo.

$ git clone https://github.com/bnahill/PyCortexMDebug

Next, in GDB, source the svd_gdb.py within the project.

(gdb) source <path/to/PyCortexMDebug>/cmdebug/svd_gdb.py

Finally, load your .svd file and start perusing!

(gdb) svd <path/to/svd>/nrf52840.svd

Loading SVD file ...

Done!

(gdb) svd

Available Peripherals:

FICR: Factory information configuration registers

UICR: User information configuration registers

CLOCK: Clock control

...

Conclusion

I have only scratched the surface of what GDB is capable of and the commands and tools mentioned here are mostly built into the application itself. The real fun begins when you start extending GDB using it’s Python API.

What are your favorite commands in GDB or Python extensions that you’ve written? I would love to hear from you in Interrupt’s Slack channel.

See anything you'd like to change? Submit a pull request or open an issue on our GitHub